BY the WAY

THE SCORE

The famous khoumei singer was sitting with the national orchestra when I came into the room over the auditorium; they were practicing an original composition written for an upcoming jubilee concert commemorating the famous singer's fiftieth birthday. When the orchestra broke for lunch and departed for the cafeteria, he and I settled on a couch by the upright piano to talk. He lauded the efforts of the orchestra members, so many of whom he had taught and mentored, for using Tuvan solo instruments and ancient solo singing techniques to create a new ensemble sound. "They are on a quest to find a future for Tuvan music," he said enthusiastically, adding, "Quests are good." I'd heard the orchestra perform its western-sounding arrangements employing Asian instruments, throat-song corralled into choir-loft harmonies, pieces read from page scores set on music stands, played to a regular four/four beat pounded out on a former shaman's drum. It was pretty, this music, but I told the famous singer about a young man I'd heard play a few days earlier, a kid really, fifteen or sixteen years old, a student at the arts academy, and when I'd visited his classroom he had sat down with a two-stringed egil and begun to bow, and to sing low in the back of his throat a different music entirely. The sound was the antithesis of tame, was desolate and consoling, ghostly and mature, and complex in a way that would be difficult to capture in any standard notation; it was rhythm-less, would drift and seize, would wait suspended through long stretches of shadowed delirium only to tumble into a transforming phrase in a quick, clear tumult, like a dammed stream finding the dam. He droned and lilted and as the piece drew near to ending, he touched the strings lightly and released a flurry of whistling crystal harmonics. Later, out in the taiga, I would watch him help slaughter a sheep and butcher it and see him gallop past on a horse, herding livestock with the same skilled abandon he brought to plucking Tuvan melodies from a Martin Backpacker guitar, sitting on a fence rail while the sheep meat boiled on the wood stove in the yurt and the women made blood sausage with the entrails, but here in the classroom, in the city, the wild certainty spoke from his egil through the chatter of teachers and visitors, the clattering of high heels as a secretary came and went, and I said to myself: here is the real thing. The famous singer asked me, who is this kid? I didn't know his name, I said, but I'd taped his song, and I found the track on my voice recorder and played it for him. He held the tiny speaker to his ear a while, and then smiled, nodded knowingly. "Menge," he said. "From the west. His uncle was a renowned player. . . Yeah, that's Menge." I could tell this tapped into some serious, satisfying secret within the singer, and I asked what would happen if Menge's music could be set down in a score and played by this ensemble, could become part of the quest for the future of Tuvan music. The smile faded. "If he even heard this," the famous singer said, motioning to the room around him, all the ancient instruments reposing in wait for the modern orchestra to return from the cafeteria, "it would break him."

LOVE & CATASTROPHE

"The balance of the world was disturbed. Something went terribly wrong. What we call creation is a cosmic imbalance, a catastrophe. Things exist by mistake. I'm ready to . . . claim that the only way to counter it is to assume the mistake and go to the end. We have a name for this. It's called love. Isn't love precisely this kind of cosmic imbalance?

Love for me is an extremely violent act. Love is not 'I love you all.' Love means I pick out something, and--again it’s a structure of imbalance--even if this something is just a small detail, a fragile individual person, I say I love you more than anything else. In this quite normal sense, love is evil." -- Slavoj Žižek

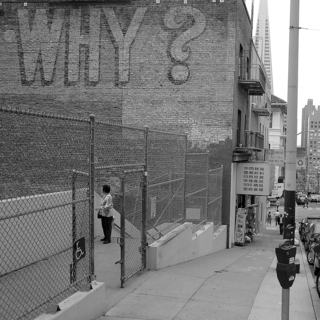

THE CORRIDOR

The train from Boston South Station to Penn Station in NYC is always a fantasy journey through old New England mill yards and along the Connecticut coast, more intimate than road travel because the world never turns its commercial face to the tracks. Instead of calculated retail glare, you peer into backyards and fields, quarries, dumps and swamps, and it's a strange thing to be riding in the great conqueror of wilderness through the wilderness preserved by its right of way. And along with messy nature: infrastructure, the rib and tendon of an unglamorized civic utility. On a snowy winter weekday, all this was swept by another mystery, the farms and marinas and empty shipping yards bundled against the season, and the landscape seemed to levitate off of the frozen earth, and perception was reversed: whatever was close, made immaterial by a frenzy of snow and speed, could not be grasped, while the far horizon was sharp to the eye, as patient and gradual and slow to pass as a thing remembered, even as it melted into distance and stillness and white.

WHAT CREATIVITY LOOKS LIKE

On a visit to New York, I stumbled into the William Kentridge exhibit at MOMA, and was lost to myself and to everything and everyone else for the rest of the day. The projections of his animation (such as "The Nose" and "Automatic Writing") were wonderful, but I especially loved his mechanical-opera version of "The Magic Flute," produced on a guignol stage, and "Chambre Noir," in which household objects (a desk lamp, a compass) interact mysteriously with drawings and films, set to a beautiful score by Philip Miller. It admonished me what real creativity looks (and sounds) like.

(See Quick Links for YouTube videos of Chambre Noir.)